Aleksandra's Note:This increasingly timely analysis by historian Carl Savich was written in 2002, over a decade ago. At that time, it was being said that Gavrilo Princip "was all but forgotten." Now, as we near the 100th anniversary of the start of World War One, Gavrilo Princip will be anything but forgotten, as his name will once again become prominent as we mark a huge historical milestone. He was and remains permanently "infamous" for a single act on a single day in a single moment in time. The question of who he was will not be the controversial issue. The issue will be "what he was" as defined by historical context and our personal perspectives. Carl Savich, in his excellent analysis of the historic roles played by Ireland's Patrick Pearse and Bosnia's Gavrilo Princip, addresses that provocative issue of "definition" in a way that will leave you wanting to learn more and perhaps reconsidering your own perceptions.

Sincerely,

Aleksandra Rebic

*****

"Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori."

("It is sweet and glorious to die for one’s country.")

- Horace, Odes, III, 2

"Breathes there a man with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

This is my own, my native land?

Whose heart hath ne’er within him burn’d

As home his footsteps he hath turn’d

From wandering on a foreign strand?"

- Sir Walter Scott, Lay of the Last Minstrel, VI (1805)

"Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel."

- Samuel Johnson, James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson (1775)

This is my own, my native land?

Whose heart hath ne’er within him burn’d

As home his footsteps he hath turn’d

From wandering on a foreign strand?"

- Sir Walter Scott, Lay of the Last Minstrel, VI (1805)

"Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel."

- Samuel Johnson, James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson (1775)

*****

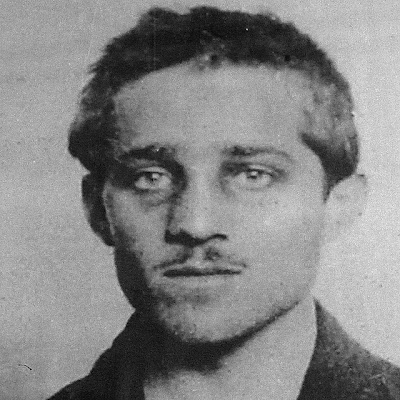

Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip

Ireland's Patrick Pearse

Bosnia's Gavrilo Princip and Ireland's Patrick Pearse - Heroes or Terrorists?

By Carl Savich

Gavrilo Princip

The role of individuals in shaping events has been a primary focus of history. Why this or that person? Did the individual cause the event or did the individual merely participate in the event? Was the event inevitable, due to chance, or caused by an individual? What role did the individual play in the historical event and why?

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie on Kosovo Day, or Vidov Dan, June 28, 1914 by Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo precipitated World War I, the Great War, a conflagration that engulfed the entire globe. Was this a random, spontaneous act, sui generis, or was it merely the culmination or crystallization of events that preceded it? Who was Gavrilo Princip? Was he just a cog, a pawn, a cipher, at the right place at the right time?

In "Searching for Gavrilo Princip" (Smithsonian, August, 2000), David DeVoss characterized the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip as follows:

"The assassination was one of the defining events of the 20th century, touching off World War I. By the end of 1918, more than a generation of Europe’s best lay dead in the trenches. But who was Gavrilo Princip?"

DeVoss illustrated perfectly and succinctly the dichotomy between patriotism, regarded positively, and nationalism, regarded negatively and pejoratively, between a freedom fighter and a criminal terrorist. DeVoss noted that while Princip was regarded as the greatest hero in Bosnian history since 1914, since the 1992 Bosnian Civil War his heroic standing had dissipated. Like in George Orwell’s 1984, Bosnian history was rewritten and revised by the Bosnian Muslim faction. From "greatest Bosnian hero," Gavrilo Princip had become the "greatest Bosnian villain." Princip went from hero to scoundrel. DeVoss concluded that, today, Gavrilo Princip is "all but forgotten?" But the more important question is: By whom? And why?

One man’s hero/freedom fighter/patriot is another man’s scoundrel/terrorist/suicide bomber. But when we deconstruct the rhetoric and propaganda, we find that nationalist movements throughout history and across cultures, religions, and societies, have been guided by the same ideals, by martyrdom and self-sacrifice. The way Western historiography judged the legacy of Gavrilo Princip was as follows: If Gavrilo Princip’s role advanced the Western position/agenda on the characterization/justification of World War I, he was assessed a positive or neutral role in Western history; he was a national hero. But if his role was deemed antagonistic to the Western conception of its role in World War I, his role changed to a negative one; he was a scoundrel. Has Gavrilo Princip been "all but forgotten" by historians and by Bosnian Serbs? Certainly Princip is not "all but forgotten” with them. But then who has 'forgotten' Gavrilo Princip? Who regards him as "a criminal terrorist"? DeVoss obviously refers to the Bosnian Muslim faction in Bosnia but without explicitly stating this, using the meaningless and misleading term "by Bosnia." But is this not absurd and totally preposterous? Moreover, it is patently false. Has the Bosnian Serb population been polled and queried, or does their view matter at all? How can Gavrilo Princip be a hero from 1914 to 1992, but a scoundrel and villain, 'a criminal terrorist', after 1992? Is history being falsified and manipulated? How is this change in historical standing to be explained? DeVoss explained this change in historical stature as follows:

"I soon realized that although he was a national hero prior to Yugoslavia’s early 1990s disintegration into warring factions, he was now considered a criminal terrorist by Bosnia."

According to DeVoss, Gavrilo Princip was not only a "terrorist" but a "criminal terrorist," an oxymoron and tautologically meaningless term. Is there such a thing as a "legal" terrorist? Was Vladimir Jabotinsky a legal terrorist in advancing Zionism? Was George Washington a "legal" terrorist in committing murder and treason against the British Government in advancing separatism/secession? Or were they, too, "criminal" terrorists? Or were they "freedom fighters"? Was Osama Bin Laden a “freedom fighter,” a mujahedeen, when he was part of the Bosnian Muslim Army during the 1992-1995 Bosnian civil war and a "terrorist" when he targeted US military forces and civilians? Is the change only nominal/rhetorical/propagandistic, or is it real? Do our labels change or do the things they represent change? Has Osama Bin Laden changed since we armed and trained him in the 1980s to fight the Russians as part of the mujaheeden forces in Afghanistan? Why do we label Osama Bin Laden a “terrorist” now? Earlier he was a "freedom fighter." What is terrorism? How is terrorism to be defined? Isn’t this merely history as propaganda? Who was Gavrilo Princip?

Patrick Pearse was a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland. His rebellion was an act of self-sacrifice and martyrdom on behalf of his nation. The goal was to achieve the independence of Ireland from Britain. Like Gavrilo Princip, Patrick Pearce was guided by a national tradition and myth of self-sacrifice and martyrdom to achieve freedom for one’s people or country. Gavrilo Princip was guided by the Kosovo myth of the martyrdom of Prince Lazar and Milos Obilic who gave their lives so that the nation might endure. Patrick Pearse was guided by the Irish myth of Cuchulainn who transcended death by a self-sacrifice for the Irish people/nation. A comparison of the two cases demonstrates that nationalism, patriotism, and rebellion have been unchanging and constant throughout history and have the same features and qualities in every society, country, religion.

Gavrilo Princip being apprehended

after the assassination in Sarajevo June, 28, 1914

Gavrilo Princip in custody after the assassination 1914

The assassination on June 28, 1914 by Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918) of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie precipitated World War I, the Great War, one of the largest global conflicts in history. The resulting conflict resulted in the deaths of 5 to 10 million soldiers and led to the overthrow of the Hohenzollern, Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman Empires/dynasties. But who was Gavrilo Princip? What was the reason behind the assassination?

The assassination in Sarajevo in 1914 did not occur spontaneously or sui generis but was the culmination and end result of a chain of events that began with the 1875 Bosnian insurrection or rebellion against Ottoman Turkey. Bosnian historian Vladimir Dedijer stated that "this fateful murder," the assassination in Sarajevo, "was itself the climax of many long generations of struggle by the Slavs of southern Europe against Austrian and Turkish tyranny." Gavrilo Princip’s grandfather, Jovo Princip, his father, Petar Princip, and his uncle Ilija Princip, were part of the 1875 insurgency that began in the Grahovo Valley of Hercegovina. The major stronghold of the insurgents in Hercegovina, Crni Potoci (The Black Brook), was just outside the Princip house. The leader of the insurgency in the Grahovo Polje region of Hercegovina was the Serbian Orthodox priest Ilija Bilbija, who was from the same village as the Princip family and who later would christen and choose the name for Gavrilo Princip. The Princip family, originally known by the name Cheka, was a kmet or serf family living in Gornji Obljaj below the Dinara Mountain range that divides Bosnia and Dalmatia. The village is in the Grahovo Polje region with the Korana river passing through it.

Bosnia-Hercegovina was occupied and ruled by the Muslim Ottoman Turkish Empire for over 400 years. Beginning in 1463, Bosnia was invaded and conquered by the military forces of the Ottoman Turkish Empire. The Grahovo Valley became a military frontier zone, called the kapetanija. The matrolozi was an auxiliary military branch made up of Christian forces. In the 1700s, members of the Princip family were part of the matrolozi. The kmets of Bosnia-Hercegovina lived in a zadruga, or extended communal families who under the ciftlik system paid a tax that went to both the state and the feudal landlord. The feudal landlords also requested corvee, or unpaid labor, from the kmets. The kmets had to perform work on the landlords property. The tax burdens on the impoverished kmets resulted in a series of agrarian/peasant revolts in Bosnia-Hercegovina, in 1807, 1809, 1834, 1852-1853, 1857, and 1858. The Safer Decree of 1859 established the tax regimen for the kmets, who were reduced to tenants on the land: One tenth of their crops were to go to the state, while one third was to go to the feudal landlord, who had full, hereditary title to the property upon which the kmet worked. The kmet of Hercegovina enjoyed minimal/limited civil and human rights.

Arthur Evans observed in 1875:

"The kmet lies … at the mercy of the Mahometan owner of the soil as if he were a slave…He is thus allowed to treat his kmet as a mere chattel; he uses a stick and strikes the kmet without pity, in a manner that no one else would use a beast."

The kmets paid a house tax, a land tax, a cattle tax (Porez), a hog tax (Donuzia), and a sheep and goat tax (Resmi Agnam). The 1875 insurrection began in Hercegovina due to a poor crop yield. Facing starvation and impoverishment, the kmets launched a rebellion that spread to Bosnia. In support of the Serbian revolt in Bosnia-Hercegovina, Serbia and Montenegro declared war on Ottoman Turkey. Turkey was militarily defeated following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. At the 1878 Conference of Berlin, however, Bosnia-Hercegovina was transferred to the Austro-Hungarian Empire to administer and occupy. The rising expectations of the Serbian population were not realized. Expecting independence and self-determination, instead, one master was replaced by another. The lot of the kmet improved very little. The Austro-Hungarian Empire sought to maintain the status quo in Bosnia. Agrarian and political and social reforms were not forthcoming. Instead, Austria-Hungary sought to ensure its occupation and administration of Bosnia. This was the historical milieu for the assassination in Sarajevo in 1914.

Gavrilo Princip was born on July 25 (July 13 by the old Julian calendar) in 1894 in Obljaj, in the Grahovo region of Bosnia-Hercegovina, the son of a postman, Petar, whom Princip referred to as "a peasant, but engages in business." Gavrilo Princip’s parents, Petar and Maria Nana nee Micic, had nine children, five sons and four daughters, six of whom died in infancy.

Princip attended primary school in Grahovo where he excelled in his studies, especially in romantic and historic literature. A teacher at the school gave him a collection of Serbian heroic folk poetry. At thirteen, Princip planned on a military career and went to Sarajevo to study at the Military School. Instead, he wanted to pursue a business career so he enrolled in the Merchant’s School where he studied for three years. He was described as “reserved,” “quiet,” “sentimental,” “always earnest, with books, pictures,” “very fond of reading,” and "a passionate reader.” Princip was described as having an “inferiority complex” because of his small build and lack of physical strength. Instead, Princip relied on books and literature and poetry. He read the romances and novels by Sir Walter Scott and Alexandre Dumas. Following his third year, he left the Merchant’s School to attend the Tuzla gymnasium (High School.) He admitted that he was an atheist and not very observant of religious customs but turned to romantic literature and epic poetry and political tracts instead. In a colloquy with Dr. Martin Pappenheim in 1916 during his imprisonment, Princip’s obsession with books and reading is described:

"Solitary, always in libraries… Always a reader and always alone, not often engaging in debates… Read much in Sarajevo… Had a nice library, because he always was buying books…. Read many anarchistic, socialistic, nationalistic pamphlets, belles letters and everything… Bought books himself… Always accustomed to read…"

Princip stated that "books for me signify life." He wanted to become a poet and wrote poetic verses.

In 1911, he joined the Young Bosnia Movement (Mlada Bosna), a group made up of Serbs, Croats, and Bosnian Muslims, committed to achieving independence for Bosnia. Princip became politically active. In February, 1912, he took part in protest demonstrations against the Sarajevo authorities for which he was expelled. Following his expulsion, he went to Belgrade. While crossing the border, he kissed the soil of Serbia. In Belgrade, he sought to gain admission to the First Belgrade High School but failed the entrance exam. In 1912, Serbia was abuzz with mobilization for the First Balkan War. The members of Young Bosnia (Mlada Bosna) were volunteering to join the Serbian army. Princip planned to join the committee, irregular Serbian guerrilla forces under Serbian Major Vojislav Tankosic which had fought in Macedonia against Ottoman units. Tankosic was a member of the central committee of Unification or Death (Ujedinjene ili Smrt.) Princip, however, was rejected by the committee in Belgrade because of his small physical stature. He then went to Prokuplje in southern Serbia where he sought a personal interview with Tankosic. Tankosic, however, rejected Princip because “you are too small and too weak.” He was determined to compensate for his lack of physical stature and the underestimation of his abilities that he was subjected to. Dedijer argued that his rejection was “one of the primary personal motives which pushed him to do something exceptionally brave in order to prove to others that he was their equal.” Princip thus wanted to take part in the major events of the time, the military campaign against Ottoman Turkey and the impending conflict with Austria-Hungary. Denied a role in the armed forces, he sought to find another way to strike a blow for Bosnian independence. Ironically, he would fire the first shot of the Great War, World War I.

Princip and the members of Young Bosnia led ascetic lives, abstaining from tobacco, alcohol and sexual relations. They became committed, disciplined, hard-core militant revolutionaries. They had all resigned to give up their lives for the struggle to achieve independence and unification. They took the motto “unification or death” literally. After the assassination of the Archduke, they planned to commit suicide by taking cyanide caplets. The Young Bosnia Movement was committed to violence and revolution, not gradual, peaceful reform. Change would only come with violence, with action. Princip explained this difference as follows:

"Our old generation was mostly conservative, but in the people as a whole there existed the wish for national liberation. The older generation was of a different opinion from the younger one as to how to bring it about… The older generation wanted to secure liberty from Austria in a legal way; we do not believe in such liberty."

What was the driving and overriding motive that guided Princip? The Young Bosnia Movement was made up of all three major Slavic groups in Bosnia-Hercegovina: Orthodox Serbs, Roman Catholic Croats, and Bosnian Muslims, although Serbs were the largest group. Their goal was the unification of all the South Slavs into a single state, a state that would be independent and sovereign. There would be self-rule. Unification by whatever means necessary was the objective. Unification presupposed independence from Austria-Hungary and sovereignty. Gavrilo Princip and the members of Mlade Bosne saw their actions as advancing the goals of independence and unification, even if their own lives would be sacrificed in the struggle. Princip expressed this desire for self-sacrifice as follows:

"There is no need to carry me to another prison. My life is already ebbing away. I suggest that you nail me to a cross and burn me alive. My flaming body will be a torch to light my people on their path to freedom."

Unification was the goal of German and Italian nationalism in the 19th century which in turn was inspired by French unification and nationalism. Serbian and Irish nationalism followed the same pattern and historical dynamics. At his trial in 1915, Princip explained his motive: “We thought: unification, by whatever means.” But who or what were to be unified? Princip considered himself a “Yugoslav” first and a “Serbian” second. In its broadest and most general form, unification would consist of all the South Slavs. In its narrowest form, it would consist of the unification of only Serbs, consisting of an enlarged Serbia, termed “Greater Serbia” by Austria-Hungary. In essence, Young Bosnia represented the culmination of the Yugoslav idea, the unification of all the South Slavs into a single state, Yugoslavia. The reason Princip is “all but forgotten” today is because the “Yugoslav idea,” Yugoslavian unity, is discredited now. In 2002, the “third” Yugoslavia was officially dissolved and a “new” country was formed, Serbia and Montenegro. But in 1914, the Yugoslav idea was a major and guiding principle of Balkan nationalism. Princip explained his nationalist goals as follows:

"I am a Yugoslav nationalist and I believe in the unification of all South Slavs in whatever form of state and that it be free of Austria…. The plan was to unite all South Slavs. It was understood that Serbia as the free part of the South Slavs had the moral duty to help with the unification, to be to the South Slavs as the Piedmont was to Italy."

At his trial, Princip stated that he and the other conspirators, such as Danilo Ilic, shared the same nationalist views of a united South Slav state, Yugoslavia. The prosecutor asked: “What kind of political opinions did Ilic have?” To which Princip replied: "He was a nationalist like me. A Yugoslav…. That all the Yugoslavs had to be unified."

The prosecutor asked Princip: "How did you think to realize it?" Princip replied: "By means of terror. That means in general to destroy from above, to do away with those who obstruct and do evil, who stand in the way of the idea of unification."

A second motive was revenge. Princip stated: "Still another motive was revenge for all torments which Austria imposed upon the people." Princip was quoted as saying that “revenge is bloody and sweet.” What did Princip seek to avenge? Bosnia-Hercegovina was occupied and “administered” by Austria-Hungary since 1878. In 1908, Austria annexed Bosnia outright. The Serbian Orthodox population of Bosnia was denied any civil, political, or human rights. The Austro-Hungarian governor of Bosnia, Oskar Potiorek, advocated a blatantly and virulently anti-Serbian policy and opposed any measures which would improve the lot or position of the Serbian population of Bosnia-Hercegovina. Princip was motivated by the grievances and suffering of the Bosnian Serb population. The prosecutor asked him: "Of what do the sufferings of the people consist?" Princip replied:

"That they are completely impoverished; that they are treated like cattle. The peasant is impoverished. They destroy him completely. I am a villager’s son and I know how it is in the villages. Therefore I wanted to take revenge, and I am not sorry."

Opposition to Austro-Hungarian occupation and administration in Bosnia was long-standing and widespread. Political assassination attempts were common. Princip himself was guided by the earlier assassination attempt by the Bosnian Bogdan Zerajic, who headed the secret society Sloboda (Liberty). Zerajic attempted to assassinate General Marijan Varesanin, committing suicide after the attempt. Zerajic became a detested scoundrel (referred to as “scum” by Varesanin himself) to the Austro-Hungarian officials but a hero and martyr and symbol of resistance to the Young Bosnia Movement. Viktor Ivasjuk, the Austro-Hungarian chief police investigator, to show his contempt, later used Zerajic’s skull as an inkpot. Zerajic set the example to Princip to follow. When the prosecutor asked Princip: “Do you know anything about Zerajic?” Princip replied: “He was my first model. At night I used to go to his grave and vow that I would do the same as he.” A cult developed around the legacy of Zerajic who stated “we must liberate ourselves or die” which had earlier been the motto of the 1875 insurrection. He was reported to have said before he died: “I leave my revenge to Serbdom.” He was buried in an unmarked grave. But his grave was discovered by the members of Young Bosnia and became a shrine for the Bosnian nationalist movement. Princip placed flowers and soil from “free Serbia” on his grave which he brought back from his first stay there. Before the assassination, Princip paid a final visit to Zerajic’s grave. In 1912 Princip had sworn an oath that he would avenge his death. So Princip saw his actions as a continuation or fulfillment of what had been set in motion earlier.

A cult of martyrdom and self-sacrifice was fostered around the assassination attempt of Zerajic. Vladimir Gacinovic, like Zerajic, a member of Liberty (Sloboda), wrote a series of articles, which appeared in the periodicals Zora and Pijemont, “To Those Who are Coming,” and “The Death of a Hero,” wherein he argued that “a new, bright ethic is being created, the ethic of dying for an idea, for freedom.” Gacinovic wrote: “We, the youngest, have to make a new history… Youth must prepare for sacrifices.” Zerajic was transformed into “the first martyr” and the “symbol” for the Young Bosnia Movement. Zerajic established the policy that political assassination could be used as a means to achieve independence. There were seven similar assassination attempts in Bosnia before 1914. The Zerajic legacy reinforced the idea that the assassination of a “tyrannical foreign ruler is one of the noblest aims in life.” This itself was echoing the Kosovo myth, central in Serbian history and in Serbian nationalism and religious history. The Kosovo myth/legend was crucial in understanding the assassination in Sarajevo, which took place on June 28, or Kosovo Day, Vidov Dan.

The Kosovo myth was revived due to several factors. The 19th century was dominated by romanticism and nationalism which glorified heroism and emotion over reason. Serbian nationalism and literature thrived in this milieu. A symbiotic relationship resulted where each reinforced the other. Johann von Goethe, Alexander Pushkin, Walter Scott, Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, Adam Mickiewicz, and Lord George Byron, who read Bosnian Serb poetry with much enthusiasm, died in Greece as a volunteer against the Ottoman Turks, were all influenced by Serbian epic folklore on Kosovo, who then in their turn encouraged/influenced Vuk Karadzic and Petar Njegos to preserve the epic Kosovo folklore and songs and legends. Sir Walter Scott translated Serbian epic poetry on Kosovo into English, while Pushkin translated them into Russian, and Mickiewicz into Polish. In 1809 Napoleon Bonaparte created the Kingdom of Illyria consisting of Slovenia, Dalmatia and the Military Frontier, which revived the idea of South Slav unification/federation and represented the genesis of the Yugoslav idea. Influenced by Adam Czartoryski, Serbian Ilija Garasanin began devising plans for uniting Serbian-populated areas of the Balkans. Croatian Roman Catholic Bishop Josip Strossmayer was an advocate of South Slav unity as well and corresponded with Garasanin on the formation of a unified South Slav state. The Yugoslav idea, the unification of all South Slavs in a single state or federation, was developing and evolving.

The Kosovo myth was revivified by the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 against the Ottoman Empire. The First Balkan War of 1912 resulted in the defeat of Ottoman Turkey by a combined coalition made up of Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Montenegro, and Greece. This event created the precedent of the South Slavs achieving independence on their own, without Great Power intervention, which gave an added stimulus to the Young Bosnia movement. Moreover, the First Balkan War saw the Serbian army retaking Kosovo after 500 years under Turkish occupation/rule. The First Balkan War created an unstoppable momentum shift and rejuvenated Balkan aspirations for independence, sovereignty, and self-rule.

There was a dichotomy in the Bosnian nationalist movement on whether to pursue a policy of “mass revolution” or one of violence or terror. Was change to be gradual, evolutionary, and peaceful or was it to be immediate, revolutionary, and violent? Was political reform and independence to be achieved by legal, peaceful means, or, on the contrary, at the end of a barrel of a gun? There was not unanimity or consensus on this issue in the Serbian/Croatian/Bosnian Muslim/Slovene nationalist movements. But the Young Bosnia Movement, influenced by anarchist writings of Pyotr Kropotkin, the Russian Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will), a populist revolutionary organization, Giusseppe Mazzini, the leader of the Italian unification/nationalist movement, who advocated political assassination as a means of achieving independence, Giovane Italia, (the Young Italy Movement), and the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. Influenced and guided by these models and events, Young Bosnia chose the end of a barrel of a gun.

But Gavrilo Princip did not need to look far for an ideology of martyrdom or self-sacrifice. Central to Serbian national/religious/political life is the Kosovo ethos or myth. The Kosovo myth created the ethos of martyrdom and self-sacrifice to achieve freedom in Serbian history. But what was the Kosovo myth? At the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, Prince Lazar met the Ottoman Turkish forces under Sultan Murad I. During the battle a Serbian commander, Milos Obilic, was able to infiltrate the Turkish lines and was able to assassinate Murad by stabbing him with a knife in the stomach. Murad later died from his injuries. Both Prince Lazar and Obilic were executed by the Turks. Lazar and Milos Obilic were enshrined as heroic martyrs in Serbian history emphasizing the ideal of self-sacrifice for the nation, people, and church and martyrdom for liberty and freedom. The Kosovo myth became the unifying idea during the over 500 years of Ottoman Turkish occupation that preserved Serbian national consciousness and the Orthodox Church and that united Serbs as a people. The Kosovo myth was similar to the Cuchulainn myth in Irish national history and tradition. In both myths, self-sacrifice for the nation or people leads to a transcendence of death. Dedijer explained the role of Kosovo in Serbian history: “The Kosovo legend took on the meaning of a powerful ideology of rebellion against foreign rule.” British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans emphasized the enduring power of Kosovo:

“The memory of Kosovo, one of the greatest battles of the world, decisive even in its indecisiveness, remained alive up to contemporary times.”

American journalist John Reed also noted the power of the Kosovo myth. One of the conspirators in the assassination, Vaso Cubrilovic, explained the connection between Milos Obilic and Gavrilo Princip:

"The Serbs carry on a hero cult, and today with the name of Milos Obilic they bracket that of Gavrilo Princip; the former stands for Serbian heroism in the tragedy of the Kosovo Field, the latter for Serbian heroism in the final liberation."

Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was the culmination of the Kosovo ethos of self-sacrifice and martyrdom on behalf of one’s people or nation. Gavrilo Princip was the modern-day Milos Obilic. Archduke Franz Ferdinand was the modern-day Sultan Murad I.

Vladimir Dedijer explained the Kosovo ethos of self-sacrifice in The Road to Sarajevo as follows:

"No doubt in the social psychology of the South Slavs there have existed these elements of the mentality of persecuted groups, of martyrdom for a higher cause, as in the history of the Jews, the Irish, and the Poles. This irrational motive can become a reality in the process of great political strife. A similar phenomenon was observed in the thinking and action of Padraic Pearse, a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and an outstanding member of the Irish Volunteers, who distinguished himself in the Dublin uprising in 1916. He urged the necessity of an uprising against all odds and against all military reasoning in order to emphasize the importance of self-sacrifice for the cause of Ireland. This irrational attitude produced a rational result in the fact that only a few years after Pearse’s execution, Ireland secured Home Rule."

Self-sacrifice and suicide as a redemptive act is common in Serbian, Irish, and Jewish history. In Judaism, martyrdom is defined in the Kiddush ha-Shem as follows: “that everything within man’s power should be done to glorify the name of God before the world.” In Judaism, martyrdom consists of a religious and a national component. A martyr commits suicide to both glorify God and to liberate his nation and people from occupation and political oppression. In the Kiddush ha-Shem, “every Israelite is enjoined to surrender his life rather than by public transgression of the Law to desecrate the name of God.” As Dedijer noted, Kosovo was to Serbian Orthodoxy and nationalism what the West or Wailing Wall of the demolished Beth Hamikdash temple in Jerusalem was to Judaism.

Disaffection and opposition to Austro-Hungarian occupation and rule in the Balkans was widespread and endemic. Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats sought independence and self-rule themselves. In other words, the independence movements were not solely limited to Serbs. Many Bosnians shared the views and goals of Gavrilo Princip and the Mlade Bosne Movement. Bosnian Nobel Prize winner Ivo Andric, an advocate of Yugoslav unity himself, in his diary entry for June 8, 1912, in commenting on the attempted assassination of Governor Slavko Cuvaj by Luka Jukic, supported the policy of political assassination:

"Today Jukic made an attempt on Cuvaj’s life…. Long live those who are dying on the pavements, expressing so well our common misfortune."

Gavrilo Princip was a product of the age. Mlade Bosne did not emerge spontaneously or sui generis but evolved and developed out of the 1875 insurgency in Hercegovina. Gavrilo Princip was the culmination of all that had gone before. He lived in an era when war was the prevailing ethos. The period before the Great War was an era obsessed with violence and with war, with a naïve conception of warfare which was quickly becoming anachronistic by the end of the nineteenth century. In From Sarajevo to Potsdam, A. J. P. Taylor characterized the age and the social milieu/mood/climate or civilization as follows:

“European civilization is whatever most Europeans, as citizens, were doing at the time. In the period covered by this book, they were either making war or encountering economic problems. Therefore war and economics make up their civilization.”

It was an age that believed that issues could be resolved at the end of a barrel of a gun.

Gavrilo Princip was tried in Sarajevo in 1915 and found guilty, but, because he was under the age of twenty, he could not be sentenced to death. Instead, Princip was sentenced to 20 years in prison. He died of tuberculosis on April 28, 1918 in the Theresienstadt prison in Austria.

Patrick Pearse

Like Gavrilo Princip, Patrick Henry or Padraic/Padraig Pearse/MacPiarais (1879-1916) resorted to violence and rebellion/insurrection to achieve the goals of Irish nationalism. Princip and Pearse were motivated by the same ideals: nationalism and independence/sovereignty for their respective nationality/ethnic groups.

Patrick Pearse was a commander of the Irish Easter Rising of 1916, an insurrection against British rule in Ireland. Pearse was also the President of the Provisional Government formed after the proclamation/declaration of an independent Irish republic. In Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption, Sean Farrell Moran examined the role that Patrick Pearse played in the Easter Rising of 1916 in Ireland. The “uprising” began on Monday, April 24, 1916, at the General Post Office in Dublin when an Irish republican leader brandished a gun declaring the independence of the Irish Republic. British troops then attacked the “rebels” with guns and artillery. The “insurrection” lasted for a week until finally put down by British military forces which included Irish veterans from the Western front in France. Approximately 450 “rebels” were killed and 2,000 were interned. The British troops suffered casualties of 100 killed or wounded in the conflict. Patrick Pearse was a central figure in the uprising.

First, Moran noted that “historians of Ireland widely regard Dublin’s Easter Rising of 1916 as the most important event in modern Irish political history” and that Patrick Pearse “was the most important figure of the Easter Rising.” Historians of Ireland have not made Pearse or the Rising very “comprehensible” and Pearse remains “enigmatic” because Irish historiography has been “conventional in approach” and “conservative in tone.” Moran faulted "the literature on Pearse” because it has failed to “draw critical connections between Pearse and the historical event.” Historians have not shown how an individual such as Pearse could come to play the role he did in the Rising. Historians have not used “innovative methodological approaches.” Moran then examined the historical literature on Pearse and the Rising and concluded that it has “by and large...failed” because a conventional, rationalistic historical approach is inadequate to explain Pearse and the Rising. The rationalistic approach assumes rationality when in fact Pearse was motivated by irrationality. Instead, Moran applies a psychological analysis of Pearse and of the Irish nationalist tradition by exploring and examining in depth both Pearse’s childhood and life and the ancient Irish national myths. For only by examining these aspects can one gain an understanding of the notions of self-immolation, of blood sacrifice, redemptive violence, for Pearse clearly understood the suicidal and futile nature of the Rising, but which he saw as a symbolic act of redemption, a “blood offering” in the name of Irish nationalism. Moreover, Pearse’s martyrdom was not a futile and meaningless act but was a calculated and thought-out action that was part of a longer Irish tradition of martyrdom. For Pearse and those who would follow him, his martyrdom had meaning and impacted Irish history and nationalism. Furthermore, Moran argued that Pearse was in a sense merely expressing a “sentiment of his age”, the idea that national and personal redemption could be achieved through violence and death. Rupert Brooke and Charles Peguy were discussed, who like Pearse, saw a similar need for redemption in a suicidal act.

Moran pointed out the irony of Pearse’s suicidal act when he compares the Rising to the Great War, World War I, which was a suicidal act of redemption on a massive scale. It is estimated that between 5 and 10 million people died in the Great War. Verdun became a tragic symbol of the waste of young life, an offensive launched not to achieve any tangible military objective, but to bleed France white. In the process, hundreds of thousands died needlessly. There is an old Roman saying attributed to Horace that guided the combatants on all sides during the Great War, which loosely translated, is as follows: It is sweet and noble to die for one’s country. Seen in this broader context, Pearse’s act is rendered more comprehensible. Pearse lived in a time when patriotic nationalism was at its zenith, when Theodor Herzl founded Zionism, when the Balkans erupted in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, when Bosnia was in turmoil, and when the nationalities problem consumed the Habsburg Empire. Indeed, the act that precipitated the Great War, World War I, was very similar to Pearse’s act, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914 by a Bosnian Serb “nationalist,” Gavrilo Princip, who was a member of the Young Bosnia Movement. The assassination occurred on June 28, St. Vitus’ Day, or Serbian Vidov Dan, Kosovo Day, the date commemorating the epic battle of Kosovo in 1389. So like Pearse, Princip too was guided by redemptive violence as a blood sacrifice for the assassination was clearly as futile and suicidal as Pearse’s act was. Princip too was guided by a nationalist mythology of redemption, of sacrifice for a nation and people. So seen in this broader context, Pearse and the Rising can be seen in proper perspective.

Patrick Pearse was born on November 10, 1879 in Dublin, the son of an English father and Irish mother. In “The Making of a National Hero,” Moran detailed Pearse’s childhood and formative years and his family and social relationships. Diaries, Pearse’s unfinished autobiography, reminiscences of friends and associates, Pearse’s own writings, plays, articles, poems, and essays were examined in depth. Pearse emerges as a human being and we are able to see what motivated and inspired him. Clearly, Pearse was a product of his age, of his time, and of his environment. He became a militant Irish nationalist, took up the cause of Irish national identity, became immersed in Gaelic language, culture, and history. But we also see the inconsistencies and the wavering and the lack of commitment to a single, unified ideology as Pearse struggles to find his role and function.

In “The State of Ireland,” Moran examined the political climate of Ireland at the turn of the century by examining the key Irish nationalist parties and movements, the literary societies, the Gaelic League, and the Celtic Revival in Ireland. Irish independence was clearly the key issue of Irish politics of Pearse’s time and for generations before. The constantly evolving Home Rule debate continued unabated. The emergence and growth of Sinn Fein and the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood (IRB) are examined and discussed. Pearse was a member of the IRB. This chapter presents the political climate in which Pearse lived. It was a climate of volatility and of violence and of opposition to England.

The next chapter examined the “politics of redemption” by a “psychodynamic” analysis of the tradition of violence in Irish history. Moran maintained that to sacrifice themselves for a cause wholeheartedly required “a concept of the nation” that had psychological depth and meaning for the individual, that abstract and theological considerations were not enough. Ernest Jones’ analysis of Ireland as an “island home” is presented. Seeing Ireland as a feminine figure who has been violated demanded redemptive violence and sacrifice. This identification was reinforced by Irish Catholicism, by Irish poetry, and by Irish mythology from the Tain. The Young Ireland Movement continued this identification through poetry which relied on a Gaelic past. The ancient myth of Cuchulainn is crucial in Irish national mythology because of its theme of transcending death through sacrifice for the nation. In a nation that had a history of being conquered and of rebellion, such a myth was all-important. This tradition was similar to the Kosovo epic tradition in Serbian history, folklore, and poetry and the martyrdom of Prince Lazar and Milos Obilic. Like Gavrilo Princip, Patrick Pearse was immersed in an epic/heroic history of self-immolation or suicide to redeem his people and nation from defeat and oppression. The Young Ireland Movement had much in common with the Young Bosnia Movement which in turn was based on the Young Italy Movement. The 18th century was one of nationalism. Both Princip and Pearse were the embodiments of this nationalist tradition. Moreover, the 19th century saw much violence in Ireland which inspired a poetry of sacrifice and a tradition of symbolic violence and death, indeed, an “eroticization of death.” This chapter is important in showing the roots of Irish nationalism, of the peculiar Irish mindset regarding national independence. Moran has chosen the right material, the mythological sources of Irish nationalism and the poetic works which most eloquently evoked it.

Next Pearse’s career as a journalist and school teacher were examined. Pearse was clearly talented as a writer, but was not a major literary figure. He was what might be termed a minor writer. Pearse wrote plays and short stories for children and nationalist articles, mainly on Gaelic language and culture. He found his true strength to be in speaking where he made his key contribution. Politically, Pearse was considered “naive” and “ignorant.” Pearse’s commitment to violence and death as redemptive acts transformed his thinking and vision for Irish nationalism. His vision became clear, unwavering, and committed. He gradually became accepted by the IRB, who were looking for someone who was articulate and single-mindedly committed to the cause of Irish independence. Pearse stated: “Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.” The stage was now set for the Rising. Moran offers an analysis of why Pearse changed as he did. Pearse never married and had few close social contacts outside of his family. He thus had no object for his psychic energy. Thus, he sublimated his energy in Irish nationalism, and in the Rising. This material is important in showing the motivations behind Pearse’s actions.

In the chapter on the Rising itself, Pearse’s own writings and poetic works are quoted and examined to show the thought processes of Pearse just before the Rising. This is an excellent method of elucidating the motivations behind the Rising. Here, however, some of the weaknesses of the analysis emerge. For instance, who was Roger Casement and what was the relationship of Germany to the Irish independence movement? Was there a long history of German involvement, or was it only during the Great War, was it merely a sham or was a German invasion plausible? At this point, the broader political context of the Rising is not fully developed. Casement and the German involvement is only sketched out. What was Pearse’s involvement with Casement if any? Here, a more in- depth political discussion is needed. Moreover, we are not told of the broader implications for the nationalist movement and its members? What happened to Clarke? What happened to the IRB and Sinn Fein?

The final chapter is on the European “revolt against reason” typified by the Great War itself. Moran explained that the Rising was not the result of a rational process, but resulted from “deep-seated psychological and emotional conflicts” which emerged after the failure of constitutional initiatives. The Rising was a “revolt against modernity,” which England represented; it was a revolt against reason. At a time when thousands of Europeans were dying daily on the battlefields of the Somme, at Verdun, Pearse’s sacrifice does not seem so inexplicable. It was an age when people actually believed that violence and death, which war is, would lead to national salvation and rebirth. It was a throwback to a much earlier time, to a mythic notion of the nation. It is noble and sweet to die for one’s country. Pearse was not alone in seeking salvation through sacrifice and death. The entire age was consumed by the same desire.

The style of the narrative is flawless. The writing is lucid, clear, and uncluttered. Only what was needed is said and nothing more. There are no diversions. The narrative is direct and the flow is unrelenting and consistent throughout. The lucidity and clarity impart a tremendous power to the narrative. Because there are no diversions, there are no interruptions and the text is very readable. The book is well written and well edited.

The methodologies employed are appropriate for the subject matter. A psychological analysis is crucial in understanding the motivational makeup of an individual. Examining diaries, personal reminiscences and letters is essential in understanding what the actors thought and what motivated them. A strictly political analysis could not provide that. A political analysis also would not explain the mythological roots of Irish nationalism and the role of language, in the form of literature, in creating a national consciousness. Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption is an excellent introduction to the Irish nationalist history and important in any understanding of Pearse and the Rising. Moran’s balanced and objective analysis throughout is crucial in making the events of that period comprehensible.

Pearse surrendered unconditionally to British forces “to prevent further slaughter of Dublin citizens.” He was court-martialed and executed, along with his brother Willie, by a firing squad on May 3, 1916 at the Príosún Chill Mhaighneann - Kilmainham prison in Dublin.

The Easter Proclamation of 1916 proclaiming

Ireland's independence from the UK

read aloud by Patrick Pearse April 24, 1916

Conclusion

Nationalism, patriotism, and rebellion are common to all cultures, nations, religions, and societies. Martyrdom and self-sacrifice on behalf of the nation are common ideals. Gavrilo Princip and Patrick Pearse embodied these ideals in seeking to achieve independence for their respective nations. This is what emerges when the rhetoric and propaganda is deconstructed and analyzed. Their importance or role in history does not change, but our evaluation of their significance and role changes. Moreover, the evaluation changes for different groups and strata and nations. One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter. Indeed, one man’s freedom fighter is the same man’s terrorist at different moments in time. Only the labels change, but what they label does not change. The evaluation depends on who is doing the labeling, or who is writing the history. The danger here is that history becomes merely propaganda, a fantasy construct based in delusion and absurdity.

Gavrilo Princip. Patrick Pearse. Were they national heroes or scoundrels and criminals? Freedom fighters or suicide bombers? Heroes or terrorists?

________

Bibliography

Clark, Edson L. Turkey. NY: The Co-operative Publication Society, 1878.

Dedijer, Vladimir. The Road to Sarajevo. NY: Simon and Schuster, 1966.

DeVoss, David. “Searching for Gavrilo Princip.” Smithsonian. August, 2000. Vol. 31, number 5.

Evans, Arthur John. Through Bosnia and Hercegovina on Foot. London: Longmans, Green, 1877.

Holbach, Maude M. Bosnia and Herzegovina: Some Wayside Wanderings.NY: J. Lane Co., 1910.

Moran, Sean Farrell. Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption: The Mind of the Easter Rising, 1916. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1994.

Owings, W.A. Dolph. The Sarajevo Trial. Cherry Hill, NC: Documentary Publications, 1984.

Pappenheim, Martin. “Dr. Pappenheim’s Conversations with Princip.” Current History, August, 1927, pp.669-707. (Translation of German Gavrilo Princips Bekenntnisse (Gavrilo Princip’s Confession). Vienna: Lechner Sohn, 1936.)

Taylor, A. J. P. From Sarajevo to Potsdam. NY: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., 1966.

Carl Savich is a historian with an M.A. in History and a J.D. in Law. His articles have appeared on numerous websites and newspapers.

*****

If you would like to get in touch with me, Aleksandra, please feel free to contact me at heroesofserbia@yahoo.com

*****