Aleksandra's Note:One of the best publications ever issued about the Kosovo legacy is KOSOVO by William Dorich, published in 1992. If you can find the book, get it. Dorich's beautiful tribute includes an essay by Thomas Emmert which should be a must-read for anyone searching to understand what the legacy of Kosovo is all about.

It should also be a must-read for Serbs who need to be reminded about this legacy and why it is essential to preserve and protect their sacred KOSOVO.

Sincerely,

Aleksandra Rebic

*****

"THE KOSOVO LEGACY"

by Thomas Emmert

On 28 June, 1389 an alliance of Serbian and Bosnian forces engaged a large Ottoman army on the plain of Kosovo in southern Serbia. When the battle was over, Prince Lazar, the commander of the Christian army, and Murad, the ruler of the Ottomans, lay dead. In the years and centuries that followed, the battle and the martyred Prince Lazar became the subjects of a rich literature of popular legend and epic poetry that has profoundly influenced Serbian historical consciousness. The bard, the storyteller, and, eventually, the traditionalist historian depicted the Battle of Kosovo as the catastrophic turning point in the life of Serbia; it marked the end of an independent, united Serbia and the beginning of 500 years of oppressive Ottoman rule. The legend of the battle became the core of what we may call the Kosovo ethic, and the poetry that developed around the defeat contained themes that were to sustain the Serbian people during the long centuries of foreign rule.

A feeling of despair permeated Lazar's lands after the prince's death and his wife's surrender to the Ottomans the following year. Conscious of the need to combat pessimism in Serbia and to provide hope for a bright future, the monastic authors of the day wrote eulogies and sermons in praise of Lazar in which they interpreted the events of this troubled period for their own contemporaries. In their writings Lazar is portrayed as God's favored servant and the Serbian people as the chosen people of the New Testament: the "new Israel." Like the Hebrews in Babylonian captivity, the Serbs would be led out of slavery to freedom. Lazar's death is depicted as a triumph of good over evil: a martyrdom for the faith and the symbol of a new beginning. Serbia and her people would live. Responding to contemporary needs, the medieval writers transformed the defeat into a kind of moral victory for the Serbs and an inspiration for the future. The Serbian epic tradition only developed these ideas further and established them soundly in the consciousness of the Serbian people.

Lazar's hagiographers also endeavored to legitimate Lazar's rule in Serbia. If Prince Lazar could be viewed as part of a continuous line of authority that had begun with the Nemanjici and that would continue after Lazar, it might be possible to overcome the sense of disorder and chaos which had characterized the troubled years 1355-1389. These writers wanted to see their own society as an integral part of the Nemanjic tradition. In giving legitimacy to Lazar, they sought to identify Lazar's Serbia and Nemanjic Serbia as one and the same entity.

After establishing this continuity of leadership, the medieval writers had to deal with the Battle of Kosovo itself. The battle is given very little detail in these earliest Serbian sources, and there is no indication that it was a decisive Serbian defeat. The Serbs had sustained substantial losses in the battle - and yet Murad and a multitude of his troops had been killed and Bayezid, the new sultan, had retreated in haste to Edirne to secure the throne. Serbian writers were, therefore, not concerned with describing a great military defeat. Rather, the central theme in each Serbian account is the death of the Serbian prince. In the view of his eulogists, Lazar sacrificed himself so that Serbia might live. What they were conscious of was the fact that the battle robbed Lazar' s principality of its strength and leadership. Lazar' s death paralyzed Serbian society. He represented the last and only hope against the Ottomans, and it is for this reason that his death was seen as the great tragedy of Kosovo. When the enemy returned again, there was no one to oppose them, and Serbia' s fate was sealed.

In the 15th century the emerging epic tradition of Kosovo began to express new themes, particularly the assassination of Murad by a courageous Serbian knight, Milos Obilic, and the suspicion of betrayal at the battle.

The epic tradition of Kosovo would develop much more detail and many more themes and characters during the centuries of Ottoman rule in Serbia. In the 100 years after Kosovo, however, we can discern the origins of the major themes that were to give shape to the cult of Kosovo: the glory of pre-Kosovo Serbia; the necessity of struggle against tyranny; and the essential link between the Kosovo ethic and Christianity, which was expressed most clearly in the heroic ideal of self-sacrifice for the faith and for Serbia, the futility of betrayal, and the assuredness of resurrection.

Throughout the centuries after Kosovo its legacy and its unique ethos played an important role in the preservation of Serbian identity. With the establishment of Ottoman rule in the Balkans, those Serbs who remained in the mountains or who fled there to find refuge preserved the ancient tribal traditions of that remote mountain life. The mountains became the protector of the cultural and ethnic characteristics of Serbian patriarchal society. Moreover, encouraged by the Serbian Church, this society carried on the memory of an independent Serbian state. The Church romanticized the Nemanjic tradition for the masses and, removing any negative feudal connotations, helped to create the image of a once glorious state. Lazar' s death on Kosovo was the atonement for all of Serbia' s sins - sins that had called the wrath of God upon them in the first place and caused them to lose their state.

When these mountain Serbs began to colonize other parts of the Balkan peninsula, they brought with them both their patriarchal ideas and the memory of an independent Serbia. This patriarchal society encouraged a feeling for justice and social equality. According to the argument of Vasa Cubrilovic, it was the democratic, patriarchal aspirations of the Serbian village which gave a social-revolutionary tone to the eventual wars for Serbian national liberation. In this society Serbs came to believe that there can be no free state without a struggle.

These democratic, patriarchal ideas are seen most clearly in the oral epic poetry that is an expression of Serbian society during the Turkish rule. The epic poem is a chronicle in verse through which the Serbs expressed their past at a time when they had no state of their own and when most of them were illiterate. Only those events that were important for them and for their fate became subjects of the epic tradition. The result is that the epic contains a peculiar periodization of history in which events that were viewed as turning points in the history of the Serbs became so important that earlier developments were all but forgotten.

It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Serbs viewed the collapse of the medieval Serbian state as the central event in their history and sought an explanation for it in the Battle of Kosovo. Indeed, the epic cycle of Kosovo became the longest, the most beautiful, and the most important of all the Serbian epics. The roots of such a development were clearly established soon after the battle in the eulogies and sermons composed in the memory of Prince Lazar. The Church nourished the ideas in these writings during the centuries of Turkish rule, and the patriarchal society accepted them and added its own visions, attitudes, and experiences to create the epic tradition of Kosovo.

In a most recent study of the epic Svetozar Koljevic argues that the decasyllabic poems of the Kosovo cycle emerged among illiterate peasant singers in the culture of exile as Turkish conquest brought about the collapse of feudal society. The poetic form of feudal society was known as bugarstice, poems in 14 to 16-syllable lines. Koljevic suggests that Kosovo poems in this form did appear on the Adriatic in the 15th century but that it was the decasyllabic poetry which became the primary medium for the Kosovo epic. The illiterate singers picked up fragments and themes of the story of Kosovo and shaped them in their new poetic expression which was to last for centuries. On the Adriatic the oral epic would have an influence on written literature, finding its way most importantly into the history of Mavro Orbini and the prose legend, Prica o boju kosovskom (Tale of the Battle of Kosovo).

The highly moralistic society of the Serbian village is clearly reflected in the epic tradition. Such virtues as courage, honor, justice, and respect for tradition were fundamental to the ethos of the village and the epic. This was a society which refused to accept the right of any man to rule another; thus we discover in the epic the glorification of those brave men who fought against tyranny. Milos Obilic, the assassin of Murad, represented the ideal hero who sacrifices himself in order to strike a blow against tyranny. The epic interpreted sacrifice for the good of society as the noblest of virtues and inspired the Serbs to countless struggles and sacrifices in the cause of liberation. The legendary tradition of Kosovo encouraged brigandry and revolutionary acts against the Ottomans throughout the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries.

By the late 18th century as the spirit of revolution found an echo in the Balkans, Serbs were ready to utilize the powerful psychological factor of Kosovo in the struggle for liberation and unification. The Serbs of the Vojvodina gave the cult of Lazar a kind of national character and warmly embraced the written legend of Kosovo which was embodied in the 18th century Prica o boju kosovskom (Tale of the Battle of Kosovo). As we have seen, this legendary account of the battle appears to have originated in the south in the general area of Montenegro, the Bay of Kotor, and Dubrovnik. It came north during the migrations and was copied and widely disseminated during the 18th century. In this way a society found inspiration for its national awakening in the legendary tale of its medieval past.

Destroying tyranny, liberating the land of all foreign control, and reuniting all Serbs in one strong state were primary goals among Serbs in the 19th century. The Serbian Revolution of 1804-1815 created a new Serbian society and was a partial fulfillment of that agelong dream of avenging Kosovo and liberating Serbia. Perhaps the best exemplar of this revolutionary spirit and one of the greatest interpreters of the Kosovo ethic was the prince and poet Petar Petrovic-Njegos, ruler of Montenegro during the second quarter of the 19th century. For Njegos life consisted of war against the Turks, and the spirit and memory of Kosovo dominated his actions and writings. Njegos was himself a product of the Dinaric highlands, that rugged, barren land which produced a unique people. The Yugoslav anthropologist Jovan Cvijic in his study of the social psychology of the South Slav peasantry argues that the people from these highlands demonstrated a unique personality which he labeled the "violent dinaric type." Milos Obilic displayed some of the characteristics of the Dinaric type, and the mountain peasants of Njegos' time remembered the personal sacrifice of the Kosovo assassin in the experiences of their own revolutionary environment.

In his most important work, the epic poem Gorski vijenac (Mountain Wreath), Njegos gave expression to this heroic element in the folk tradition of his own people as he paid tribute to the memory of Kosovo. In the poem the word "Kosovo" (along with "God") is mentioned most often, while Milos Obilic is referred to no fewer than 12 times. It was this epic poem, in fact, that helped to give the final shape to the image of Obilic as the pure, Christian hero - the symbol of freedom. Njegos' message was clear. Encouraged by the long centuries of Ottoman rule and the spirit of the Kosovo epic, Serbians were to understand that the noblest of acts was to kill the foreign tyrants. Njegos' "Mountain Wreath" in itself had an enormous influence on the Serbian national movement in the decades following its publication in 1847, and was of special importance among those Serbs who remained rural and uneducated. In Njegos' hands the legacy of the Kosovo martyrdom was transformed into a compelling, positive force determined to eliminate the foreigner from all South Slav lands.

During the 19th century, the spirit of Kosovo also found new expression in the talents of Serbia's dramatists, poets, and painters, who were attracted to the artistic possibilities embodied in the national legend. Inspired by the wars for liberation, the theme of Kosovo reached the Serbian stage in the first half of the 19th century. Sima Milutinovic Sarajlija wrote the first play on the subject of Kosovo. His Tragedija Obilic was crafted in 1827 and finally published in Leipzig in 1837. This was followed by 5 other Kosovo dramas: Milos Obilic ili Boj na Kosovu by Jovan Popovic in 1827; Car Lazar by Isidor Nikolic in 1835; Car Lazar by Matija Ban in 1858; Milos Obilic by Jovan Subotic in 1866; and Lazar by Milos Cvetic in 1889. Apparently, the public expected to find characterizations in these dramas which mirrored their understanding of Kosovo from the epic and the legendary tale. In a critique of all 5 works written in 1890 Milan Jovanovic protested the poetic license of his nation's dramatists:

"The titans of Kosovo, who should amaze the public from the stage as they did 5 centuries ago from the stage of world history, have in the course of several decades become miserable pygmies in the hands of our dramatists. They ... exert all their strength to cover up the absence of their goals with ornate but hollow phrases."

Kosovo also became a favorite theme for some of Serbia's 19th century painters. Inspired by the nationalism of the early part of the century, the Romantics found popular subjects in the heroes and events of the Battle of Kosovo. They portrayed Lazar as a strong, vital, secular emperor whose image could evoke sentiments of pride in the population of a revolutionary age. Among those who chose some aspect of the Kosovo tradition for their canvas were Petar Cortanovic, his son Pavle, Pavle Simic, Novak Radonic, Djura Jaksic, Adam Stefanovic, and the Croatian painter, Ferdo Kiderec. Later in the century the first generation of Serbian realists showed little interest in the heroes of Kosovo; but among the second generation of realists Kosovo was a subject in works by Paja Jovanovic, Ivan Rendic, Marko Murat, Djordje Krstic and Uros Predic, who in 1917 painted the famous Kosovo Maiden, now part of the permanent collection at the National Museum in Belgrade.

While the spirit of Kosovo encouraged the struggle for independence and was an important source of inspiration to Serbs throughout the 19th century, the road to complete liberation would not be easy. Many of the Serbian lands, including Kosovo, remained under foreign control during most of the 19th century. Prince Njegos certainly reflected the impatience and the desires of many in his constant demands for vigilance and continued sacrifice against the Ottomans. In the Vojvodina newspaper Napredak (Progress), 50 years after the revolution, an article expressed frustration over the relative lack of progress in the unification of Serbia and hinted that the problem resulted from a lack of understanding of the spirit of Kosovo:

"Our successes have been small. Half of the Serbian nation still remains in Kosovo chains. An indifference toward our basic responsibilities is the main shortcoming and the most harmful sickness of our people. Even the most powerful and bloody examples cannot cure us from this disease ... and today we put little effort into knowing our Milos."

And in a lecture in Novi Sad in 1872 Emil Carka observed that things would have been much better in Serbia if its leaders had demonstrated the same devotion to the ethos of Kosovo as its common fold had:

"If everything had been decent among us after Kosovo as it was with the common people, we would be much more progressive today. But everything - theocracy, aristocracy, and bureaucracy - failed us. Only the common folk remained truthful to their task. Only they preserved the testament of Kosovo."

In 1876, Serbia found itself at war with the Porte on behalf of its fellow Slavs in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The failure of this South Slav insurrection guaranteed that Serbia would exist at the mercy of the big powers for the rest of the century. Thus, by the time of the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo in 1889, Serbia was under Austrian influence and her plans for unification were necessarily thwarted.

The first suggestion for a 500th anniversary celebration was made in 1886 in the Novi Sad newspaper Zastava (The Banner). Nothing came of the first appeal, however, and near the end of 1888 Zastava suggested that the Serbs in Ruma should organize a celebration since Ruma was near Vrdnik where Prince Lazar's remains were preserved. Finally on January 1, 1889, Zastava announced that a formal committee had been organized in Ruma for the Kosovo commemoration.

Belgrade newspapers im-mediately protested this development and demanded that any celebration be held in liberated Serbia. On February 6, 1889, Male Novine (The Little Newspaper) insisted that the commemoration should be observed in Krusevac, Lazar's medieval capital. The Serbian government quickly took the initiative and submitted a set of suggestions for the celebration to the regency, which included: (1) a commemoration in all parts of Serbia; (2) the laying of a foundation stone in Krusevac for a monument to the heroes of Kosovo; (3) state support for the printing of new editions of the Kosovo epic; (4) the establishment of a new Order of Prince Lazar which would be awarded only to the Serbian ruler and his heir apparent; and (5) the coronation of Aleksandar Obrenovic as King of Serbia in the monastery of Zica as a part of the celebration. On April 12, 1889 it was announced in Belgrade that a commission of 15 had begun to organize the main commemoration to be held in Krusevac. Both Ruma and Belgrade, therefore, had commissions for official celebrations; their plans progressed simultaneously.

As the day of the commemoration drew near, tensions began to mount in those South Slavic areas controlled by Austria-Hungary. As of April 1889, no one was permitted to travel in the empire without a great passport, and no Serbs were given such passports for travel in any southerly and easterly directions. Imperial police began to guard all roads which faced Serbia and deterred any Serb who wished to travel during the 2 or 3 days before the actual celebration. And the authorities did what they could to stop plans which were already underway. They seized the committee's funds for the celebration in Ruma and also confiscated 2,000 commemorative medallions in Novi Sad. They required the bishop of Budim, Arsenije Stojkovic, and the archbishop of Vrsac, Nektarije Dimitrijevic, to inform their priests and teachers that they were forbidden to give any sermons or talks on the subject of Kosovo or to hold any kind of commemorative meeting. In some areas of Hungary, presidents of Serbian choral societies were told that their organizations would be abolished if they participated in the Kosovo commemoration.

Sympathetic newspapers attempted to demonstrate their frustration with these restrictions. In Novi Sad Branik (The Defender) complained to the government because of the obstacles it was placing in the way of a church holiday. The newspaper suggested that the government wanted to make the commemoration a political demonstration and that the only result of its restrictions would be to interest more people in the event. In Zagreb on June 22nd, 1889 Obzor (The Horizon) reminded the Austrians and Hungarians of the apparent double standard with which they operated. In 1881 the Hungarians had commemorated the end of Turkish authority in their own land, while in 1883 the Austrians had enjoyed a very festive 300th anniversary celebration of their showdown with the Turks at Vienna. Even one Austrian newspaper seemed to understand the consequence of political repression. In June the Viennese Vaterland argued that the Hungarian and Croatian authorities were only making the commemoration of Kosovo more popular. The paper suggested that if these authorities had not interfered, the event would have stayed within its borders.

The popularity of the event did indeed spread far beyond the borders of Serbia and the Vojvodina. In Zagreb Bishop Strossmayer encouraged the commemoration, while some of his supporters even sought an extraordinary session of the Zagreb city "opstina" so that the city could claim an official role in the commemoration. From the beginning of June in Obzor there was a concerted effort to build public support in Croatia for the commemoration. In spite of harassment from the authorities, the newspaper continued to publish whatever bits of news it had about the approaching commemoration. Although several issues were banned during the month, the paper managed to put out an issue on June 27th, which included the following:

"Whoever among the Serbs rose up to lead whatever part of his people to freedom, he always appeared with the wreath of Kosovo around his head to say with a full voice: This, O people, is what we are, what we want, and what we can do. And we Croatians - brothers by blood desire with the Serbs - today shout for joy : Praise to the eternal Serbian Kosovo heroes who with their blood made certain that the desire for freedom and glory would never die. Glory to them and to that people who gave them birth." - Obzor (The Horizon Newspaper), Zagreb, 1889.

It was such sentiment which guaranteed resistance from the authorities. Khuen-Hedervary, the Budapest-appointed ban of Croatia, prohibited all commemorations in his jurisdiction. A few days before a planned Kosovo memorial in Zagreb, the president of the committee for the com-memoration received the following decision from the government:

"To the Honorable Committee for the com-memoration of Kosovo, headed by President Franjo Arnold, in Zagreb: Regarding your petition, received on the 18th of this month, we inform you that the announced concert of celebration in commemoration of the Battle of Kosovo, which the singing society intended to perform on the 27th of this month, is prohibited, on the basis of the order of the high presidium of the territorial government of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia made on the 6th of this month."

Although the ban succeeded in preventing a large, public memorial, he was unable to stop a requiem mass in Zagreb's Orthodox church and a commemorative session of the Yugoslav Academy of Arts and Sciences. At 5:00 p.m. on June 27th the Department of Philosophy and History at the Academy hosted a public session during which lectures on Kosovo were given by Franjo Racki and Tomas Maretic.

The Serbian Royal Academy of Arts and Sciences opened the period of celebration in Serbia with a commemorative session in Belgrade on June 11, 1889. Cedomir Mijatovic, Serbia's minister of foreign affairs and a great patriot, began the festivities with an emotional, romantic address on the meaning of Kosovo:

"An inexhaustible source of national pride was discovered on Kosovo. More important than language and stronger than the Church, this pride unites all Serbs in a single nation ... The glory of the Kosovo heroes shone like a radiant star in that dark night of almost 500 years ... Our people continued the battle in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries when they tried to recover their freedom through countless uprisings. There was never a war for freedom (and when was there no war) in which the spirit of the Kosovo heroes did not participate! The new history of Serbia begins with Kosovo - a history of valiant efforts, long suffering, endless wars and unquenchable glory ... Karadjordje breathed with the breath of Kosovo, and the Obrenovici placed Kosovo in the coat of arms of their dynasty. We bless Kosovo because the memory of the Kosovo heroes upheld us, encouraged us, taught us and guided us."

These sentiments were echoed later that month in Krusevac, where the most important of the Serbian memorials to Kosovo was held. Arsa Pajevic, a writer from Novi Sad, attended the events in Krusevac and left us a typically romantic chronicle of the festivities. For Pajevic the first day was one of intense emotion - even the mountains seemed to raise their heads higher, straining as if to see that day 500 years before. The commemoration began with a service in the Church of Lazarica followed by an outdoor service of prayer for the souls of those who died on Kosovo. The metropolitan of the Serbian Church delivered the sermon, which was inspired primarily by the epic tradition of Kosovo. He concluded his brief remarks with a prayer beseeching Lazar and all the martyrs of Kosovo to intercede with God to seek His help in restoring the Serbian Empire and unifying the whole Serbian nation.

In the evening after vespers a large procession led by King Aleksandar wound its way through Krusevac to the center of the city, where a foundation stone was laid for a monument to honor the heroes of Kosovo. The site was covered with wreaths, and one of them in particular impressed the crowd. Sent to Krusevac by a Czech organization in Prague, it was made of 2,000 laurel leaves, on each of which was sewn a card with the wishes and signatures of individual Czech sympathizers. On the silk sash across the wreath were written the words: "The Czech Nation. 1389 + 27/6 1889. From Ashes to Greatness."

The 500th anniversary commemorations were more successful than anyone could have imagined. In spite of all the attempts at repression, the anniversary of Kosovo became a popular symbol in the struggle for the liberation of all South Slavs from foreign rule. To many who still yearned for their freedom, the Kosovo ethic sounded a note of hope. About 15,000 people made their way to Vrdnik for the celebration that had been organized by the commission in Ruma; and in the heart of Ottoman Serbia midnight prayers were sung in the Serbian Monasteries of Pec, Decani and Gracanica. The sentiments of many were expressed in an article in Obzor on July 1st, 1889. Although banned three times that day, the newspaper managed to publish the following:

"Opponents of the national idea must recognize that two accomplishments were made in their beautiful celebration. It brought Serbs and Croats closer together, and it ignited the smoldering embers on Lazar's grave into full flames, which will not be easy to extinguish."

The celebration also excited the imagination of Slavs throughout Europe. A Slavophile newspaper in Russia, for example, termed Kosovo the "Serbian Troy" and called on all Russians to recognize it as such. "Not to praise the memory of Kosovo in Russia," the article argued, "means treason to Slavic ethnic feeling." In Vienna, South Slav youth gathered in their respective clubs and in outdoor parties to remember the heroes of Kosovo. The Russian embassy in the Austrian city commemorated the event in their chapel with the assistance of the Serbian Academic Society "Zora" and the Croatian Academic Society "Zvonimir." In St. Petersburg there was a requiem service in St. Isaac's, while in Athens black flags flew from the city's churches. Most of the Serbian colony in Paris attended a service in the Russian church, and articles on Kosovo appeared in many French journals including Debats, Temps, Republique Francaise, Voltaire, Mot d'Ordre, and Petit Journal.

Something that was not accomplished in time for the 1889 celebration, and that would probably have prevented the competition between Ruma and Belgrade, was the transfer of Lazar's remains from Vrdnik to Ravanica. Cedomir Mijatovic got the idea for the transfer while he was on a tour of Serbia with Prince Milan in 1874. Because of the possibility of conflict with the monks of Vrdnik and with the Hungarian government, Milan was not particularly interested in the idea. In 1880, however, the Hungarian government indicated that it would not oppose the transfer if the Serbian government first secured the approval of the Vrdnik monks. Mijatovic sent the Serbian poet Milorad Popovic Sapcanin to Vrdnik with an offer of a yearly payment amounting to twice the revenue generated in Vrdnik from an average year of pilgrims. This idea was criticized openly in a letter to the Serbian press from Danilo Medakovic, an interpreter with the Russian legation, who argued that the removal of Lazar's bones from Vrdnik would lead to the Magyarization of those Serbs living in Hungary. He believed that the presence of Lazar's remains sustained the Vojvodina Serbs in their patriotism. The Belgrade newspapers, which were subsidized by the Russians, sided with Medakovic, and Mijatovic was convinced to give up his idea at that time.

A decade later Mijatovic argued again for the transfer of Lazar's remains and suggested that such an act might give Serbia a renewed sense of unity and bring an end to her political problems:

"If the interests of our people are what is in question, then it is far more important that thousands of Serbs from Montenegro, Dalmatia, Herzegovina, Bosnia, Old Serbia, and Macedonia come to the center of Serbia on Vidovdan than go to the Kingdom of Hungary ... Gathered around the body of the Kosovo martyr, we might be ashamed of our political disorder. We might feel that the ties which bind us together as one and the same people are older, more important and more sacred than the ties of party."

Nothing came of Mijatovic's appeal. Throughout the late 19th century the spirit of Kosovo was evoked on each anniversary of the battle, and priests and politicians alike reminded their people of the obligation to avenge Kosovo and unify Serbia. Until the beginning of the 20th century, however, any hope that Serbia would play the role of a "South-Slavic Piedmont" was frustrated by the actions of the big powers.

The turn of the century seemed to bring with it a new, more intense desire to alter the status quo and not only in Serbia but throughout the Balkans. Many young people living under Habsburg or Ottoman rule were especially frustrated by the factionalism, chauvinism, and narrow-mindedness of their fathers and leaders, which made unity and effective action against foreign tyranny impossible. One such youth who channeled these concerns into the works of this creative genius was Ivan Mestrovic, the most important Croat and South Slav sculptor of the 20th century.

Mestrovic tended sheep as a teenager in Dalmatia, where he learned to read the epic poetry of the Serbs in Cyrillic and was profoundly influenced by the ideas of freedom and liberation expressed in the epic of Kosovo. The centuries-long struggle of the South Slavs against foreign oppression became a dominant theme in his early sculpture. Between 1905 and 1910, he studied sculpture in Vienna and Paris and spent his summers on the Dalmatian coast in Split. One summer night Mestrovic sat with some intellectuals and artists in the People's Square in Split and listened to the dramatist Ivo Vojnovic read from his recent play on the tragedy of Kosovo, Smrt majke Jugovica (The Death of the Mother of the Jugovici). Soon after that Mestrovic developed the idea for a monumental temple in honor of the Kosovo heroes:

"What I had in mind was an attempt to create a synthesis of popular national ideals and their development, to express in stone and building how deeply buried in each one of us are the memories of the great and decisive moments in our history ... I wanted at the same time to create a focus of hope for the future, one which stands out in the countryside and under the free sky."

Mestrovic hoped that the monument would serve as a symbol of the suffering and hopes of all South Slavs. He envisioned a monumental gate with triumphal arches, a central building with a cupola, and a belfry whose columns would be representations of the Kosovo heroes. Under the cupola was to stand an enormous statue of Milos Obilic. He anticipated that like the medieval cathedrals, this monument would involve the collective efforts of several generations.

Mestrovic's obsession with the Kosovo temple continued until World War I, by which time he had completed several of the Kosovo figures. The emotional impact of this work encouraged the art historian Josef Strzygowski to suggest that there could certainly be trouble for the Habsburg Empire if "Mestrovic's fellow nationals understand his message and if his art awakes in them new ideas of unity."

While the years of war eventually ended in the creation of a South Slavic state, the tragedy of those years and the problems of the post-war period turned Mestrovic away from his faith in the spirit of Kosovo. He discovered that the appeal of Kosovo was not universal, and his search for a new inspiration led him to Christianity. "It was thinking about these ideas," he said, "that brought me back to biblical themes. A feeling for the general suffering of man took the place that until then had been filled by a feeling for the suffering of my own nation ..."

After the turn of the century the youth of Serbia were offered more aggressive outlets for their passions and idealism. The return of the Karadjordjevic dynasty to the Serbian throne in 1903 signaled a new period of independence vis-a-vis Austria-Hungary. Within a decade Serbia was at war. In the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 examples of self-sacrifice were abundant among Serbian soldiers. The realization that Kosovo could finally be liberated after more than 500 years fired the imaginations and the emotions of young Serbs. Consider the recollections of one of these young patriots as he was told that his unit was heading for Kosovo:

"My God, what awaits us! To see a liberated Kosovo. The words of the commander were like music to us and soothed our souls like a miraculous balsam. The single sound of that word "Kosovo" caused an indescribable excitement. This one word pointed to the black past 5 centuries. In it exists the whole of our sad past the tragedy of Prince Lazar and the entire Serbian people ... Each of us created for himself a picture of Kosovo while we were still in the cradle. Our mothers lulled us to sleep with the songs of Kosovo, and in our schools our teachers never ceased in their stories of Lazar and Milos ...When we arrived on Kosovo and the battalions were placed in order, our commander spoke: "Brothers, my children, my sons!" His voice breaks. "This place on which we stand is the graveyard of our glory. We bow to the shadows of fallen ancestors and pray God for the salvation of their souls." His voice gives out and tears flow in streams down his cheeks and gray beard and fall to the ground. He actually shakes from some kind of inner pain and excitement. The spirits of Lazar, Milos, and all of the Kosovo martyrs gaze on us. We felt strong and proud, for we are the generation which will realize the centuries-old dream of the whole nation: that we with the sword will regain the freedom that was lost with the sword."

When Kosovo was finally liberated in the Balkan Wars, King Peter I Karadjordjevic was on the throne. The liberation guaranteed that Peter would be remembered by some as the romantic fulfillment of the legacy of Lazar and Milos:

"He was not an ordinary king. Rather he was the incarnation of the idea of Great Serbia, the symbol of Serbian liberty and the Serbian epic, the dream of centuries, and the hope of all generations. He was the synthesis of national feelings, the soul of the Serbian people, a gentle balm and solace for those who suffer."

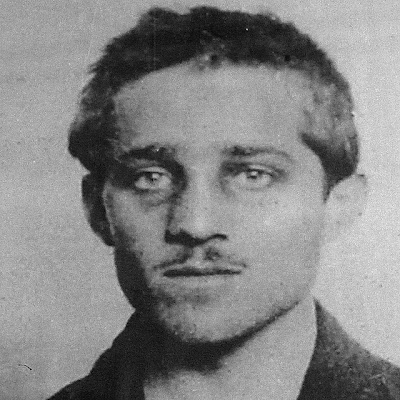

Less than 2 years after the liberation of Kosovo, Gavrilo Princip waited on the streets of Sarajevo to assassinate the heir to the Habsburg throne. A teen-ager who knew Njegos' "Mountain Wreath" by heart, Princip had certainly been inspired by Njegos' characterization of Milos Obilic as the ideal exemplar of the philosophy that the murder of a tyrant is no murder. Like other young Bosnians who were reared in the patriarchal society of the South Slav peasantry, Princip honored the legend of Kosovo. He believed that political assassination could help to restore the liberty lost on that Serbian field 5 centuries earlier. In essence, Princip was but one more example of Cvijic's Dinaric personality:

"Dinaric man burns from a desire to avenge Kosovo where he lost his independence, and to restore the old Serbian Empire, about which he constantly dreams, even in the most difficult times when anyone else would despair ... He considers himself chosen by God to carry out the national mission. He expresses these eternal thoughts in songs and sayings ... He returns to them at every opportunity ... Every Dinaric peasant considers the national heroes as his own ancestors ... in his thoughts he participates in their great deeds and in their immeasurable suffering ... He knows not only the names of the Kosovo heroes but also what kind of person each one was and what were his virtues and faults. There are even regions in which the people feel the wounds of the Kosovo heroes. For the Dinaric man to kill many Turks means not only to avenge his ancestors but also to ease their pains which he himself feels."

This was the spirit and dedication which motivated hundreds of thousands of Serbs to untold sacrifice during the tragic years of World War I. During that war, Serbia became the "darling" of both the English and French public which interpreted her determination to fight and secure her freedom as an expression of the Kosovo spirit. In 1916 a nationwide tribute to Serbia was arranged in Britain to celebrate the anniversary of Kosovo. Information about Serbia was disseminated throughout the country. A shop opened in London in order to sell literature about Serbia, which British publishing houses had printed in tens of thousands of copies. Posters created from a Punch cartoon, "Heroic Serbia" were displayed conspicuously throughout the country. Schools and churches arranged special lectures and services in commemoration of the Serbian holiday. Cinemas showed films about Serbia, and the Serbian national anthem was played in some theaters. The English press publicized all the activities with more than 400 articles and news items.

R. W. Seton-Watson, who helped organize the celebration, prepared an address on Serbia for the schools of Great Britain. Entitled "Serbia: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow," the address was read aloud in whole or in part in almost 12,000 schools and helped to acquaint the youth of Great Britain with Serbian history. In his brief remarks Seton-Watson characterized the Battle of Kosovo as one of the decisive events in the history of Southeast Europe. He wanted his listeners to understand "how completely the story of Kosovo is bound up with the daily life of the whole Serbian nation."

In June 1918, 5 months before the end of the war, the United States recognized the anniversary of Kosovo as a day of special commemoration in honor of Serbia and all other oppressed people who were fighting in the Great War. The meaning of Kosovo was the subject of countless sermons, lectures, and addresses throughout the United States.

In a special service in New York City's Cathedral of St. John the Devine the Reverend Howard C. Robbins compared Serbs to the people of Israel and observed that Serbia "voices its suffering through patience far longer than Israel's and it voices a hope that has kept burning through five centuries."

The primary commemoration was held in New York at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on the evening of June 17, 1918. James M. Beck, former assistant attorney general of the United States, endeavored in his address to draw a relationship between the ethic of Kosovo and the tragedy of the Great War:

"It is true that we commemorate a defeat, but military defeats are ... often moral victories. If Serbia is now temporarily defeated, she has triumphed at the great bar of public opinion, and she stands in the eye of the nations as justified in her quarrel. Serbia was not only the innocent, precipitating cause of this world war, but it is the greatest martyr, and I am inclined to think in many respects its greatest hero."

He then related the legend of the angel who came to Lazar on Kosovo and offered him a choice between the Kingdom of Heaven and the kingdom of the earth. Lazar, of course, chose the Kingdom of Heaven, and Mr. Beck considered this the revelation of a great truth:

"Running through recorded history as the golden thread of a divine purpose is the truth, that the nation which condones a felony against the moral order sooner or later suffers ... Each nation which took part in the Congress of 1878 had reason to regret the compounding of the felony that first started on the plains of Kosovo in 1389 ... The war is a great expiation for the failure of civilized nations for centuries to recognize the duty that ... Lazar assumed on the eve of Kosovo."

During the war, the Yugoslav Committee in London interpreted Kosovo as an inspiration for all South Slavs in their struggle against the enemy and their desire for a unified state. In a message to the Prince Regent of Serbia in April of 1916 the Committee proclaimed:

"Medieval Serbia had its Kosovo which weighed upon the Serbs for 5 centuries. The Serbia of the present after having gloriously avenged its former Kosovo, had lately suffered a second, more terrible than the first. But the Serbia of today is no longer isolated as was the Serbia of the past. Great through the universal moral prestige which the heroism and super human sacrifices of her sons have earned for her, Serbia is today supported by powerful allies. It is her desire and her duty to avenge this second Kosovo. But the country which will arise from the terrible ordeal of which we are the spectators will not be merely a restored, or even an aggrandized Serbia, but one that includes the entire Yugoslav nation, and the whole of its national territory, united in one single state under the illustrious dynasty of your reverend father. This state will be the unyielding rock against which the waves of Germanism will dash themselves in vain."

A month later the committee argued:

"For more than five centuries Kosovo was the banner of our national pride, the sum and substance of our national unity, and as it was, thus it is and will remain the watchword of every Yugoslav wherever he dwells, the watchword of a race which longs, aspires, and demands its proper place and the right of governing its own destiny among other cultured nations."

In the view of many during the war, the creation of a Yugoslav state would be the final vindication of the 14th century tragedy on Kosovo. Tihomir Djordjevic, a Serbian professor of ethnography who wrote for the English public during the war, argued that Yugoslav unity had been the ultimate goal of Tsar Stefan Dusan, and had it not been for Kosovo "a great, powerful, and free Yugoslav Empire would have grown." Kosovo was, therefore, a tragedy for all the South Slavs and necessarily became a symbol for the freedom of them all as well. Obviously, this was a view of the medieval world molded by contemporary concerns.

With the end of the war and the establishment of a Yugoslav state, the centuries-long ordeal was apparently over. During the turbulent inter-war years, the Kosovo ethic was often invoked as the essential spirit of Yugoslav unity. After the assassination of King Alexander in Marseilles in 1934, for example, there was a popular attempt to identify the king and his death with Prince Lazar and his sacrifice on Kosovo. In the words of Juraj Demetrovic, the editor of Jugoslovenske Novine (The Yugoslav News),"Alexander chose the heavenly kingdom in order to secure the future of Yugoslavia." He argued that no great idea has ever been victorious without its Golgotha. Croatia, Serbia, and Slovenia all had their individual Golgothas, but it was only the tragedy at Marseilles which represented the ultimate sacrifice. There Alexander became the first martyr for the Yugoslav idea, and resurrection would come with a strong and unified Yugoslavia.

1939 was the last year in which the anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo was widely celebrated. The 550th anniversary came at a time when the clouds of war in Europe again loomed on the horizon. The commission for the celebration of the anniversary announced to all Yugoslavs that the Kosovo ethic was, indeed, a Yugoslav ethic:

"Kosovo gave us Vidovdan from whose faith, ethic, and symbols we remained alive ... until this very day. The Vidovdan mystique was that magical lever for all our unprecedented undertakings and accomplishments in history. It was the foundation of our national, spiritual image, our heroism, and our Christian view of man. It was the greatest and most difficult test of the Serbian people, and it remained as an example not only to them but to all Yugoslavs ... Vidovdan is the torch of our spirit which is stronger than all other factors in anything we do. It is our deepest sign and warning not to forget our national duties and honor, but to be like those perfect soldiers who fell alongside the righteous prince on Kosovo for his unified nation, its happy future and honor, and for the empire of eternal national ideas."

The Serbian organization, "National Defense," designated Vidovdan as "a holiday of thanksgiving to known and unknown heroes, as a day of commemoration and remembrance for our obligations to king and country, and as a holiday for the cult of freedom and the indivisibility of the Yugoslav spirit, land, people, and state." One member of this organization encouraged an even broader interpretation of the power of Kosovo: "Kosovo is a pan-Slavic, universal idea. It can be accepted only by rejecting all selfish concerns, prejudices, and all national pretensions. "Yugoslavs everywhere were reminded that Kosovo belonged to them all. To the Croats, many of whom were less than enthusiastic about celebrating a Serbian holiday, the message was direct:

"Prince Lazar integrated the national and religious ideals. The Kosovo myth gave the Serbian people strength and created a collective consciousness. This should be a lesson to the Croatian public. On the crossroads of the world, where so many interests are in conflict, collective consciousness is necessary. Without it there is no strength, no self-sacrifice, no future."

In Slovenia the message was also an appeal to unity:

"What does this national holiday mean to us today in these extraordinary circumstances! Nothing less than our national consciousness and our strong desire to remain united, free, and independent."

The Serbian people needed no reminder of the importance of Kosovo, but the anniversary in 1939 provided another opportunity for reflection. Bishop Nikolaj Velimirovic described Kosovo as "our national Golgotha and at the same time our national resurrection." This Christian symbolism, so central to the meaning of Kosovo throughout the centuries, was expressed in dozens of commemorative articles:

"Not a single task could be started without first consulting Kosovo through the medium of the gusle. Hajduks and uskoks and captains of Kotor, and Montenegrian rulers and leaders of national uprising - all of them before everything else communed first with the miraculous Vidovdan wafer."

A 1939 article in Slobodna Misao (Free Thought), entitled "The Kosovo Religion" demonstrated that Kosovo could even be exploited to test the loyalty of individuals to the unitarist position of the Serbian monarchy. Using the examples of Stojan Protic and Velja Vukicevic, the author of the article suggested that some political leaders in the postwar period followed ideas which were not inspired by the religion of Kosovo. Apparently, there were "many ways to interpret this old religion."

It is clear today that the appeals for unity in 1939 were eleventh hour alarms. Europe was at war again 3 months after the anniversary of Kosovo. In less than 2 years the fragile unity of Yugoslavia would be destroyed. On March 25, 1941 representatives of the Yugoslav government signed the Tripartite Pact. Widespread dissatisfaction with this capitulation to the Axis powers led 2 days later to a coup d'etat in Belgrade. Patriarch Gavrilo of the Serbian Church saw the capitulation as a betrayal of the Kosovo ethic. In an address on Belgrade radio he reminded his people that Lazar had faced the enemy and accepted his fate for the sake of Serbia. He insisted that the contemporary situation demanded the same sacrifice:

"Before our nation in these days the question of our fate again presents itself. This morning at dawn the question received its answer. We chose the heavenly kingdom - the kingdom of truth, justice, national strength, and freedom. That eternal ideal is carried in the hearts of all Serbs, preserved in the shrines of our churches, and written on our banners ... "

The Axis invasion began 10 days later. Yugoslavia was dis-membered and puppet states were established in Croatia and Serbia. Within weeks of the occupation the resistance struggle began. On the anniversary of Kosovo in 1942, in an article in Belgrade's Nasa Borba (Our Struggle), an organ of the puppet government, it was argued that everything the resistance movement represented was in direct opposition to the spirit, ideals, and the legacy of the heroes of Kosovo: "It is not dangerous to lose a battle. It is not even that dangerous to lose a state ... Such losses can be made up. It is dangerous, however, when one begins to distort the truth, warp principles, corrupt ideals, and poison traditions. Then the spirit suffers, craziness overcomes it, and self-destruction crushes it ... Can the discord be greater? Can the blunder be worse? It can if the eel is exchanged for the snake, the heavenly sower for the sower of corn cockles ... if truth is replaced with lies, wisdom with foolishness, beauty with ugliness, patriotism with hatred of country ... blessing with damnation ... The defeat of a nation is either a tragedy or a comedy, depending on whether the blow comes from outside or from inside, from Providence or from a crazy mind. Our Kosovo is a tragedy. The "Kosovo without Kosovo" is a comedy - a comedy as a symbol of Njegos' curse: Lords, damn their souls ...They threw away the government and the state! Lords, ugly cowards, They become traitors of the land."

With the establishment of a socialist society in Yugoslavia after World War II, there was a marked decline in public comment on the meaning of Kosovo - most noticeably on the occasion of the anniversary of the battle. The government's ideologues and many of the war's survivors helped to create new legends about the great battles of the Partisan movement. For many years after the war the Battle on the Sutjeska was revered as a kind of Yugoslav Kosovo. Commemorations of the Battle of Kosovo were essentially confined to services of the Serbian Church; and it has been the Church that continues to remind the faithful of the basic religious and humanistic qualities of the Kosovo ethic:

"One of the main characteristics of Kosovo is the idea of a conscious, willing sacrifice for noble ideals, a sacrifice of one individual for the benefit of the rest, a sacrifice now for the sake of a better future. According to popular understanding which developed in our folk literature, the Battle of Kosovo was not an event in which it was possible to win or lose. It was rather a conscious, heroic sacrifice. A slave is only half a man; a freeman is similar to God."

A perhaps more secular interpretation of the basic idea of the Kosovo spirit is provided by Miloslav Stojadinovic in the preface of this Kosovska Trilogija (Kosovo Trilogy). He maintains that:

"... The Kosovo spirit is the revolutionary spirit of justice, humanity, equity, equality of rights, with a noticeably democratic and progressive quality of respect for the rights of all other people."

In these few words Stojadinovic expresses the timeless character of the Kosovo ethic. As we have noted, this ethic was nourished in the patriarchal society of the Serbian peasant during the centuries of Ottoman domination. It expressed a basic attitude toward life itself: democratic, anti-feudal, with a love for justice and social equality. For centuries it has been an essential ingredient in the historical consciousness of the Serbian people.

Thomas Emmert

"The Kosovo Legacy"

From KOSOVO

By William Dorich

*****If you would like to get in touch with me, Aleksandra, please feel free to contact me at heroesofserbia@yahoo.com***** +Politika+March+16,+2013.jpg)